Activism

Self-Harm Versus the Greater Good: Greta Thunberg and Child Activism

A workplace strike shows company owners and management that workers are able to harm them economically. A school strike, on the other hand, constitutes a form of self-harm, undertaken to attract adult attention.

Greta is eleven years old and has gone two months without eating. Her heart rate and blood pressure show clear signs of starvation. She has stopped speaking to anyone but her parents and younger sister, Beata.

After years of depression, eating disorders, and anxiety attacks, she finally receives a medical diagnosis: Asperger’s syndrome, high-functioning autism, and OCD. She also suffers from selective mutism—which explains why she sometimes can’t speak to anyone outside her closest family. When she wants to tell a climate researcher that she plans a school strike on behalf of the environment, she speaks through her father.

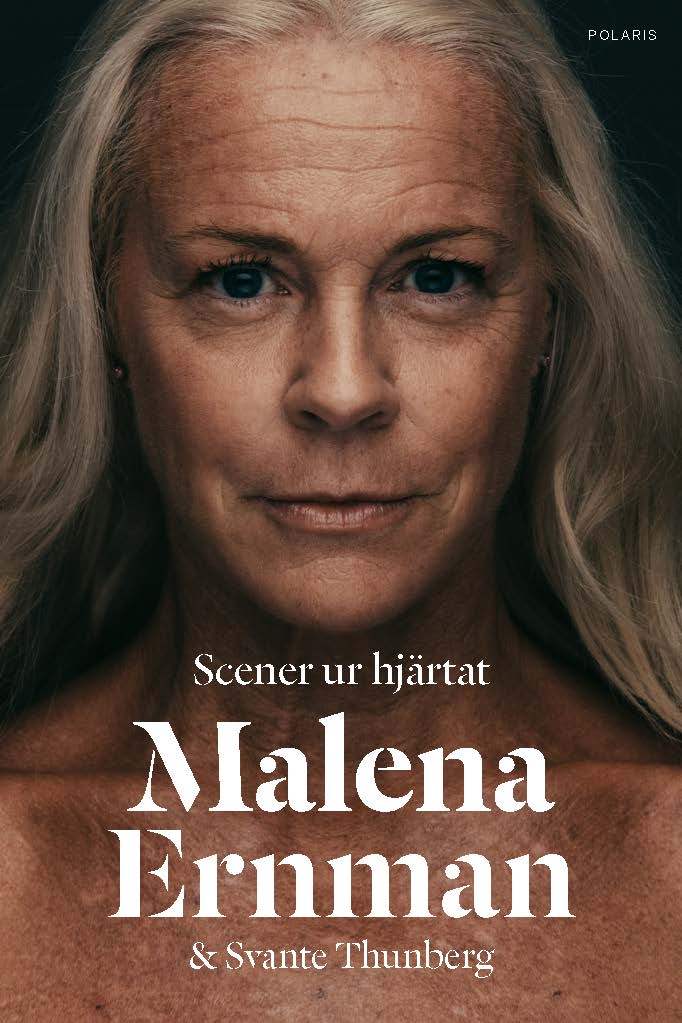

The book Scenes from the Heart (“Scener från Hjärtat,” 2018) recounts these medical difficulties and the events that led to Greta Thunberg’s now-famous “school strike for climate,” in which hundreds of thousands of children have refused to attend school to protest about government inaction over climate change. Greta herself strikes every Friday and spent three weeks sitting outside the Swedish Parliament at the beginning of the school year. Written by her family—mother, father, Beata and Greta—the story is told in the voice of Greta’s mother, the opera soprano Malena Ernman, who was a celebrity in Europe long before her daughter’s fame. Although the book is only available in Swedish for the time being, it is already being translated into numerous languages—a development that reflects the global fascination with Thunberg’s campaign.

We are offered a story of “a family in crisis and a planet in crisis”—two phenomena that are presented as inextricably linked. The book posits that oppression of women, minorities, and people with disabilities stem from the same overarching root problem as climate change: an unsustainable way of life. The family’s private crisis and the global climate crisis, the authors argue, are simply symptoms of the same systemic disorder.

Greta is not alone in her mental suffering, according to the book. Her sister Beata, who was 12 when the book was written, lives with ADHD, Asperger’s syndrome, and OCD. She is prone to sudden outbursts of anger, during which she screams obscenities at her mother. What would normally be a 10-minute walk to dance class takes almost an hour because Beata insists on walking with her left foot in front, refuses to step on certain parts of the sidewalk, and demands that her mother walk the same way. She also insists that her mother wait outside during class—she isn’t allowed to move, even to go to the bathroom. The child still ends up weeping in her mother’s arms.

Like many parents of children with similar diagnoses, Greta and Beata’s parents fight hard for their daughters to receive the right care and assistance in school. When Greta refuses to eat they do everything they can to save her from starving herself. Her father begs their doctor to save Beata from whatever it is that plagues her. To read the story is heart-wrenching, many times over.

And yet as someone who does not share the family’s political views—that the girls’ problems are inextricable from the climate crisis, and that the cure is to “change the system”—I wonder whether the world needs to know the intimate details about the lives of these two anguished young girls.

Which brings me to us—editors, journalists, prize juries, teachers, onlookers.

It has been less than a year since Scenes from the Heart was published and, during that time, Greta has become a global celebrity. This week, she was named one of the world’s 100 most influential people by Time Magazine. She has briefly met the Pope, who encouraged her to “Keep doing what you’re doing.” She has received numerous awards, including, most recently, the German Golden Camera award. She has been nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize. She has been featured and interviewed in most of the world’s leading media. She has appeared on a panel with the UN Secretary General António Guterres, addressed the European Parliament, and lunched with the Financial Times.

“Is Greta the new Che Guevara?” asked the German TV-anchor Maybrit Ilner recently during a TV debate about the striking school children.

In defense of the excellent Ms. Ilner, she probably meant to refer to Che Guevara as a global political symbol. But the question is telling: Greta is turning into a revolutionary icon.

Given what we know about Greta’s problems and challenges, is this an appropriate adult response to Greta’s school strike?

It is easy to exoticize. It is easy to look at pictures of the girl with pigtails and simply see someone out of the ordinary. Someone—or something—foreign. German media have dubbed Greta the “Pippi Longstocking of climate change,” with reference to another Swedish girl-rebel with a similar hairdo. They don’t seem to appreciate that the girl with pigtails comes from a country where her peers look more like the stars of the Norwegian television series SKAM than Pippi Longstocking—or that the girl is clearly marked by years of self-starvation. Instead they choose to portray the child as a dated cultural stereotype, based on her looks.

A workplace strike shows company owners and management that workers are able to harm them economically. A school strike, on the other hand, constitutes a form of self-harm, undertaken to attract adult attention. And the global school strike for climate is led by a girl with a long and tragic history of self-harm to her own body.

In Scenes from the Heart, when Greta eventually starts eating again, she only allows herself certain foods. Her mother has to prepare the same food every day for Greta to bring to school and keep in the school refrigerator: pancakes filled with rice. Greta will eat them only if there is no sticker with her name on the container: stickers, paper and newspapers trigger Greta’s OCD against eating.

“I want you to panic. I want you to feel the fear I feel every day,” Greta said when she addressed the world’s leaders in Davos.

Given the child’s history of precisely that—fear and panic—the adult response should perhaps not be “You go, girl” (the words of Madeleine Albright when she was asked what she thinks of Greta’s school strike), but something considerably more cautious.

Greta does not skip classes from just any school, but one for children with special needs. Many other Swedish families fight hard to get their children into such schools, because places are rare. According to the family’s book, however, resources will be ample for such families once we change the system—including, according to Ernman, “patriarchal structures” that she claims favor boys with neuropsychiatric disorders over girls.

I do not wish to suggest that Greta is too young to understand the consequences of her actions, nor that the challenges she faces make her unsuitable to take a stand on political issues, or even to lead a global movement. No one who has heard her address world leaders in impeccable English can doubt that she is very intelligent. Ernman also stresses that her daughter has never felt better than during her campaign for the climate. Greta herself has said that realizing that she could do something about climate change has helped her recover.

I am also not questioning Greta’s role as a public speaker, nor the power of hundreds of thousands of protesting school children, nor that climate change is an existential threat to humankind.

But adults have a moral obligation to remain adults in relation to children and not be carried away by emotions, icons, selfies, images of mass protests, or messianic or revolutionary dreams.

Greta was recently named ”Woman of the Year” by a Swedish newspaper. But she is not a woman, she is a child. It is time we stopped to ask if we are using her, failing her, and even sacrificing her, for what we perceive to be a greater good.

Editor’s note: On April 24, 2019, a substantially edited version of this article was published without the prior approval of the author. Quillette apologises for the mistake.